- Home

- Karley Sciortino

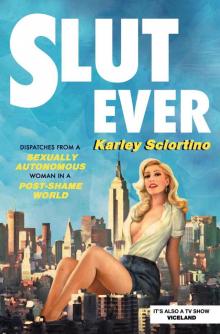

Slutever Page 16

Slutever Read online

Page 16

But despite the large number of smart, ambitious women doing sex work, there continues to be a negative, hackneyed stereotype around who sex workers are and how they got into their line of work. And it will be impossible to reinvent the image of the sex worker in the cultural consciousness until more sex workers feel safe to come out and tell their stories. As Camille Paglia said in her book Vamps and Tramps (1994): “Moralism and ignorance are responsible for the constant stereotyping of prostitutes by their lowest common denominator—the sick, strung-out addicts, crouched on city stoops, who turn tricks for drug money…The most successful prostitutes in history have been invisible. That invisibility was produced by their high intelligence, which gives them the power to perceive, and move freely but undetected within, the social frame…She is psychologist, actor, and dancer, a performance artist of hyper-developed sexual imagination.” And today—if my personal foray into sugar-babying is any indication—she is the hipster sitting next to you at your bottomless mimosa brunch in the East Village. She is your future doctor and your future lawyer.

But being “invisible” as a sex worker is a privilege. And invisibility is something that sugar babies are afforded far more than women in other parts of the industry, particularly women who do street work, or who strip, who have no choice but to be on display. The fact that sugaring allows for some anonymity does not make it in any way “better” than other forms of sex work, nor does it mean that sugar babies are smarter, or more liberated, or more chic. But sugaring is the only part of this world that I have personal experience with.

However, after spending years interviewing and making friends with sex workers in various parts of the industry—from dommes to brothel workers to strippers and beyond—I’ve come to realize that when I first entered this world, I was a bit ignorant of my privilege. The reality check came during an interview I did with Tilly Lawless, a twenty-four-year-old queer sex worker and activist based in Sydney, Australia (where sex work is decriminalized). Tilly’s a feral beauty, with a Cindy Crawford–esque mole and sandy-blond hair that hangs down to her waist. She’s the sort of girl who can post photos on Instagram of herself riding naked on a horse through a field of flowers and somehow not look like a total poser idiot. It was Tilly who first explained the whorearchy to me. What’s the whorearchy, you ask? Well, since Tilly can explain it far better than I can, here’s a comprehensive breakdown, in her own words:

The whorearchy is the hierarchy that shouldn’t—but does—exist in the sex industry, which makes some jobs within it more stigmatized than others, and some more acceptable. Basically it goes like this, starting from the bottom (in society’s mind): street-based sex worker, brothel worker, rub-and-tug worker/erotic masseuse, escort, stripper, porn star, BDSM mistress, cam girl, phone sex worker, and finishing with sugar baby on the top. Sugar baby work is the most accepted as it’s the closest to marriage in that it mimics monogamy and usually involves the exchange of material goods over cold hard cash (also, in a lot of places where sex work is illegal, sugar babying falls in a sort of legal grey space).

The whorearchy comes from both within and outside of the industry; non–sex workers will view certain workers as dirtier/more disposable/less worthy of respect than others, and sex workers themselves will often throw other workers under the bus, in order to distance themselves from them and make themselves seem more respectable. It’s driven by assumptions and prejudice. While you will find people of all different races, backgrounds, and genders etc. in all different kinds of jobs within the sex industry, racist and classist assumptions feed into the whorearchy. For instance, a non-English-speaking, immigrant woman of color will be seen as “less valuable” than me (a white middle-class woman) and further down in the chain of things. Often, more marginalized people will be forced to work in lower rungs, for example trans women of color often won’t be hired in brothels, and so have to do street-based sex work.

All sex workers are judged in this system. There is a (perceived) large gap between full-service (penetrative penis in vagina sex) and non-full-service sex work. For instance, when I crossed over from a rub-and-tug to working in a brothel, many of the girls said, “Yuck, that’s disgusting.” I have heard strippers describe themselves as “like a whore, but I keep my dignity.” Escorts describe themselves as being “high class” in an attempt to market themselves, which suggests that other workers are low class, and feeds into the whorearchy and the idea that the rest of us are worthless. (I always say: “We are not deserving of rights and respect because we are high class, but because we are human.”)

Sugar babies are some of the worst I have come across for playing into this. Because they are at the top of the whorearchy, they think they can shit on the rest of us and pretend their work is intrinsically different. “I’m not a prostitute/whore” is something I have heard time and time again from them, as if being a whore is a bad thing, or as if they don’t also suck the cock of a man they aren’t attracted to for gain.

People outside of the industry also judge you based on these misconceptions, too. A guy once said to me at a party, “Oh, but you’re pretty. Don’t call yourself a whore, you’re not like those women I see on the street, don’t class yourself with them,” meaning it as a compliment.

The whorearchy is relevant because it has a lot to do with why I’m able to casually make jokes about being a whore. Because sugar babies fall into a legal gray area in America, we are able to engage in sex work without fear of arrest, and to talk about our jobs and our goals with less risk. Women working on the streets or in brothels might be equally liberated and educated as sugar babies, but they are less likely to tell their stories, because they face more consequences when they do. (Although, of course, there have been many radical and inspiring nonsugar sex workers over the years who told their stories in hopes that one day sex workers globally will have the same rights as any other person—for example, Xaviera Hollander, Carol Leigh, Jules Kim, Pye Jakobsson, Monica Jones, and Dr. Carol Queen, to name just a few.) And putting a face and a name to a sex worker helps us to be seen as individuals, rather than as statistics, or as the reductive stereotypes we see on TV (like a street-corner crackhead or a murdered body in a dumpster).

I was recently having a conversation over Skype with Norma Jean Almodovar, a prominent sex workers’ activist and author of the book Cop to Call Girl (1994). Almodovar worked for the Los Angeles Police Department in the 1970s and early ’80s before leaving to become a prostitute, because she felt like it was “more honest work” (amazing). When I asked Almodovar what type of woman does sex work, she responded flatly, “A practical woman.” She told me, “The sugar baby phenomenon is a symptom of women being practical and saying, ‘I don’t want to put myself in huge debt for a good education.’ These women are not being forced into sex work. They have simply realized that it’s the quickest, fastest, easiest way to make a living.”

But is it actually true, as the media often portrays it, that sites like SeekingArrangement have inspired millions of middle-class women who otherwise would never have considered sex work to start selling their bodies? Or has this been going on forever, and the internet has only made it more visible? “Street walkers have always been the smallest percentage of sex workers—less than fifteen percent—and yet they get the most attention,” Almodovar told me. “Middle-class, educated women were always in the industry, advertising our services in magazines, working for high-class madams, working in safe brothels, fucking billionaires and famous actors, using our money to buy real estate and pay our tuitions—we just weren’t visible. I know a lot of sex workers who were putting themselves through college before it was ‘a thing.’”

And history supports this. For instance, a main argument in support of the birth control pill was that technology does not determine behavior—rather, technology enables behaviors that already exist. And studies have since validated this assertion: Unmarried women were having sex before the pill; it was just less out in the open. Similarly, people were having c

asual sex well before the dawn of Grindr and Tinder; dating apps have only made it more visible. And it’s no secret that prostitution was a profession of many middle-class women before SeekingArrangement brought it aboveground and triggered a moral panic. “When it comes to sex work, there are recurring periods of moral crusades, which fade out and then come back into fashion,” Almodovar told me. “People are endlessly offended by prostitution. What I find offensive is when people mind other people’s business.”

But people find great pleasure in involving themselves in the business of others, especially when it comes to women’s bodies. Throughout history, women have repeatedly been told that we don’t know what’s best for us, and that other people should be left to make decisions about our health and our bodies. Just look at the conversations around birth control, abortion, and surrogacy for proof of this. The conversation around sex work is more of the same. In 2015, Amnesty International released a draft policy on the protection of the rights of sex workers, advocating for the full decriminalization of the sex industry. In reaction, a bunch of celebrities with “an opinion”—including Lena Dunham, Kate Winslet, Anne Hathaway, Meryl Streep, and Gloria Steinem—launched a campaign opposing the proposal, stating that “regardless of how a woman ends up in the sex trade, the abuse, sexual violence and pervasive injuries these women endure at the hands of their pimps and ‘clients,’ lead to lifelong physical and psychological harm—and, too often, death.”

This statement is off base and factually incorrect. It follows a trend of inflammatory reporting on sex work that relies on inflated figures and false statistics that don’t survive any serious analysis. Of course, no one should be forced into sex work, but consensual sex work and sex trafficking are not the same thing (despite being continuously conflated). To compare a woman being trafficked to an autonomous sex worker is the same as comparing a slave to an architect.

I was particularly bummed that Lena Dunham joined this crusade, considering that she touts a message of feminism and body positivity. Not to mention that she literally makes money from being naked on-screen, meaning that she has chosen to make her body a commodity. But it seems you can only do what you want with your body if it’s something she deems to be okay. In reaction to the celebrity-led opposition, many sex workers have come forward online and essentially told these women to shut up and mind their own business. How patronizing of these (mostly privileged, white) celebrities to tell sex workers that they know more about what’s right for their bodies? Weighing in on a situation that doesn’t impact your life implies that the people who are actually impacted don’t deserve to speak. They are silencing the voices of the sex worker who says, “I do not feel exploited.” Not to mention that sex worker rights organizations, Human Rights Watch, and Amnesty International have all repeatedly pointed out that those who are truly interested in decreasing exploitation in the sex industry would be better off supporting the decriminalization of prostitution.

We should all have the right to make decisions about our own health, body, and sexuality, without fear, coercion, violence, or discrimination. And if a woman wants to finger a finance guy’s butt in order to pay her bills, then she should pursue that dream, and the rest of us should move the fuck along. As porn star and writer Stoya told me, “There are many established academics out there today who truly believe that a woman having a public sexuality keeps us down—that it’s this patriarchal plot. But porn isn’t inherently more oppressive than anything else under capitalism. The problem with this branch of feminism is that, specifically when it comes to sex work, it neglects to consider capitalism. Like, what about the demonstrable wage disparity, and the fact that you can’t have food and a roof over your head and medical care when you need it without money? And where the fuck is the money supposed to come from? Maybe [antiporn activist] Gail Dines skips to work at her office in the university, and would do her job even if she wasn’t getting paid—but that’s definitely not most people’s lives.”

Our own bodies can be tools for freedom. We can fuck for love or for fun or for money, but it should always be up to us to make that decision. And fucking for money can be more exciting than fucking for love, and fucking for fun can be more fun than fucking for money, and sometimes fucking for fun can turn out to be not so fun, because you expected it to be fun and then it was sort of boring. These are all valid experiences.

But sex work isn’t just about money or freedom or feminism or politics—it’s also about sex. Connecting money to sex is actually really hot, but it’s something that nobody ever wants to talk about. When someone is willing to pay a thousand dollars to sleep with you, you don’t need to be told that you’re beautiful. You become a luxurious sex object, a living currency, and that can be a huge turn-on. It’s impossible to have this experience with your partner because romantic relationships are too tied up in emotions. As a result, sex work provides a very unique sexual experience. People discount sex work as simply being a submission to money, or only being about power. But it’s more than that: It’s a sexual experience in itself, which is different than having sex for love or for fun.

We’re a culture that finds perverse pleasure in shaming people who don’t conform. People love to moralize, to point a finger and say, “You’re worse than me.” But shame usually has much more to do with the person doing the shaming than the person being shamed. What scares people the most about sex workers is the idea that they might actually like what they do. It forces people to admit that they don’t deplore sex work only because they feel sorry for its apparent victims, but because maybe, just maybe, sex workers are getting away with something that they’re not.

CHAPTER 5

FROM SLUT TO BI

Gay Propaganda

I don’t identify as bisexual. I just identify as a slut, which is basically the same thing anyway, right? My mother thinks so.

Until I met Alice, I never expected that I would be in a serious relationship with a woman. That’s not because I didn’t try. I mean, I’m a sex blogger—it would clearly be on brand for me to have a gay moment. Instant feminist street cred, ya know? However, while I’ve always maintained many strong female friendships, and have found myself repeatedly in awe of women in a friend-crush sort of way, up until my midtwenties my romantic experiences with women never seemed to progress further than just being a fleeting “sex thing.” I felt doomed for straightness. Sure, I was a straight girl who sometimes casually ended up with a vagina in my mouth, but a straight girl just the same.

There were a few girls over the years who gave me butterflies. Most notably JD Samson, the gender-bending drummer from Le Tigre. JD’s oversize tuxedos and sort-of-mustache had my vagina tingling in blissful confusion for most of my early twenties. Then there was my friend Jill, the delicate, heroin-chic model with a boyish figure and a cliché beat-up biker jacket whose bed I ended up in a few times during that same period. She was the first girl I ever slept with one-on-one (i.e., not in an MDMA-induced chaotic group sex situation). But with Jill, I was always unsure of whether I actually wanted to be with her, or I just wanted to be her—like, in a creepy, wear-your-skin type of way.

It was during my early squat years, when I was about nineteen, that I became friends with a group of women who I’m still close with to this day. They were a bit older than me, in their mid- to late twenties, and were all either gay or sexually fluid. I remember being intrigued and kind of envious of their relationships—they appeared to have intense levels of intimacy and understanding with their female partners. They were like regular girlfriends—they talked about periods and calories, and shared clothes and vaginal antifungal creams—but they one-upped it by adding sex (and sex that was apparently multiorgasmic, which at the time was a foreign concept to me). À la Carrie Bradshaw, I couldn’t help but wonder…is lesbianism the ultimate life hack?

“Being with women is the best,” Lolo told me. Lolo was the French, bisexual, astrology-obsessed member of our group, and at twenty-five she was in her first serious ga

y relationship. “With girls you can have sex for hours and hours, because you’re not at the mercy of the guy’s boner,” she swooned. I told her that sounded nice, but also exhausting and painful. “Plus,” she added, “you can make out forever without getting a rash, because girls don’t have beards.” That last part really resonated with me, because I happen to be quite a rashy person.

Something I loved about hanging with the lesbian mafia was the novelty of being with a group of women who didn’t devote a huge amount of time to talking about men. It was basically like that episode of Sex and the City when Charlotte becomes enamored with a group of power lesbians, and after realizing that they’ve seemingly found a loophole to male emotional ineptitude, she becomes desperate to be in their club. Except instead of a group of ubersuccessful art-world lesbians with vacation homes in the Hamptons, my lesbians were aspiring DJs chugging cheap vodka from flasks in south London squat raves. But I loved them just the same. Of course, I know the idea of “gay propaganda” is controversial. Though to be honest, these girls were a strong advertisement for team lez.

But it wasn’t until years later, just after my twenty-seventh birthday, that I met Alice. Our story begins as any great hipster romance should: at the Vice New York office. At the time, I was making a satirical sex-ed video series for the company, and Alice was called in to help with postproduction. I’d been sitting in a tiny editing cubicle chugging kombucha for twelve straight hours (as one does in a hipster sweatshop) and was on the verge of a web series–induced mental breakdown when in walked Alice: a tall, dimpled genderqueer Spanish cutie. She held up a bottle of vodka with her scrawny arm and smiled a big, toothy smile. I was sold.

Has it ever happened to you that, upon meeting a complete stranger, you instantly have the overwhelming urge to rest your head on their stomach and stay that way forever? It’s not even necessarily a sexual urge. The feeling is more abstract—more innocent, somehow. Well, that’s how I felt when I saw her. Like, it wasn’t just that I wanted to fuck her; I also wanted to stick my head under her faded T-shirt and fall asleep. About twenty minutes later, after the initial dizziness began to fade, I realized this was the first time I’d felt such crazy butterflies for a woman.

Slutever

Slutever