- Home

- Karley Sciortino

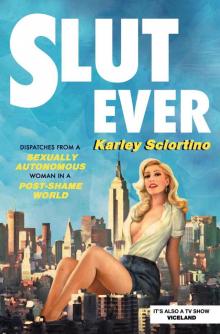

Slutever Page 17

Slutever Read online

Page 17

After that first night, I played the normal dating game—I stalked her online, intensely scrutinized the social media of everyone she’d ever dated, and then forced our one mutual friend to have a party at her apartment where we could “accidentally” run into each other again. Unbeknownst to me, this mutual friend immediately texted Alice saying, “By the way, Karley forced me to have this party as an excuse to hang out with you.” Weak move. Clearly, I showed up to the party pretending to be all aloof and casual, which made me look like a total idiot, but a cute idiot, apparently, because Alice and I ended up drunkenly banging in the hallway of the apartment building that very evening. Later that night, back at her apartment, we took a shower and I washed her hair, a uniquely sweet moment in spite of having known each other only briefly. And then I masturbated while she choked me.

After that, we became instantly and almost parasitically inseparable. And just like in my youthful lesbian fantasies, I came every time we fucked. Sometimes twice. This was a completely new—bizarre, even—experience for me after years of dating Max, whose idea of making me come was to doze off while laying his limp hand over my boob while I used my vibrator. Romantic. But Alice would ask me what felt good, and then she would just do exactly what I liked—how novel! And Lolo was right: You can have marathon sex sessions for hours, because you’re not a slave to the boner. It was a lesbian miracle. As a lesbian friend of mine said in response to the controversially long girl-on-girl sex scenes in Blue Is the Warmest Color: “Straight couples have sex for like five minutes, but lesbians have sex for like five hours, so if you look at the ratio, it makes sense that a lesbian sex scene in movie time would be twenty minutes long.”

However, despite everything being physically great, for the first few months we were together, I found it hard to fully “lose myself” during sex. Often, during particularly sweet or passionate moments, I’d suddenly become extremely aware of myself, almost as if I were looking down at us from above like a pervy guardian angel. And then I’d think: “Wait, weird…I’m, like, gay now randomly?” Clearly, this would jolt me out of the moment. It felt like such a stupid thought to be having, but I couldn’t seem to stop it from repeatedly inserting itself into my brain. Like, you know how when you go to a party wearing an outfit that’s different from what you’d normally wear, and even though you like the outfit, you don’t feel super comfortable in it yet, and so instead of being your cool, natural self, you just keep anxiously checking yourself out in the mirror? Well, that’s what being in your first gay relationship is like, in a nutshell.

These moments of hyper-self-awareness didn’t just occur during sex. Often, when we rode the subway together, Alice would put her hand on my knee and suddenly I’d think, Everyone on this train thinks I’m a lesbian. I wasn’t noting it because it made me feel bad or self-conscious; I was just registering that it was different. We all naturally become accustomed to the role we play in society and the way the outside world perceives us. Like, I’m a busty blonde who’s usually wearing a push-up bra and a pink miniskirt—I push femininity to the point of parody. When I’m out in the world, subconsciously or not, everyone perceives me as a straight girl with a low IQ. I’d grown comfortable with that. It’s what I knew. We all make assumptions about people based on the way they look all the time, and that’s totally normal and intuitive. (For instance, if you’re a guy with a ponytail, tribal tattoos, and low-rise jeans, I know that you’ve been to a sex party in the past month, and that you probably have massage oil in your man-bag at this very moment.) However, no matter what you look like, when you’re a woman holding hands with another woman, in the eyes of everyone else, you’re gay. Maybe bi, but probably gay, because bisexuality is essentially invisible in everyday life. Like, what does a bi person look like? It’s pretty much impossible to identify someone as bisexual, unless they’re literally walking down the street with a man on one arm and a woman on the other, making out with both (life goals).

Over time, this self-awareness faded as I became more comfortable in my relationship. But the most significant adjustment wasn’t getting used to being feministly fisted, or to the new way that people stared at me on the L train. It was about reassessing myself and what was important to me. It wasn’t just that I suddenly felt compelled to watch YouTube videos with titles like “The Gay Rights Movement Explained in 5 Minutes.” Yes, that absolutely happened, but it was bigger than that. After meeting Alice, I felt like I was being shown new possibilities for what my life could look like. It’s not like I was ever one of those creeps who treats life as a search for a husband. But at the risk of sounding conventional, since I was young, the vague image I had created of my future always involved a tweedy, intellectual husband, a Rosemary’s Baby–esque Manhattan apartment, and a couple of unusually gifted children. It never involved sharing tampons and yeast infection cream, or being deeply understood by my partner in ways I never thought possible (a terrifying prospect, really). But my feelings for my girlfriend were changing my idea of what forever looked like. I was like, Fuck, could this be the person who I want to make love and kale salad with forever? And this sudden shift left me staring at my reflection in my iPhone, having Zoolander-esque “Who am I?” moments.

Bisexual Demons

It probably won’t surprise you to hear that when I told my Catholic mother that I was in a serious relationship with a gender-nonbinary lesbian Jew, she basically wanted to nail herself to a cross. At first, she was mad that I had lied to her by omission, having kept the relationship a secret from her for more than a year. This, admittedly, wasn’t so cool on my part. But cut me some slack—clearly I had avoided telling my parents about Alice because I knew it wasn’t going to go over well. However, phase two of my mother’s meltdown really surprised me. What she said was “So you’re telling me that your whole life has been a lie? You’ve been a lesbian all these years and you never told me? I feel like I don’t even know you!” This was followed by waterworks, while I tried to keep a straight face (like as in literally trying to appear heterosexual).

I spent the following hours—and weeks, and months—trying to explain the reality of my situation to my her: “Mom,” I’d say, “my life hasn’t been a lie. I just randomly fell in love with a woman. It’s very Millennial.” She didn’t buy it. In fact, it made the situation even worse. In her mind, if I was gay (as she insisted I must be) it would be tragic, but at least she understood what being gay meant. She knew gay people. She thought Anderson Cooper was hot. A lesbian daughter, in theory, could give her grandchildren. But my being bi was horrifying, because if the unspeakable myth known as bisexuality actually existed, it meant that not only did I fuck women, but that I was essentially a sex-crazed zombie willing to fuck anything and everyone. Being gay was deviant, but being bisexual was just greedy, like the all-you-can-eat strip-mall Chinese buffet version of sexual orientation.

This perception of bisexuality is not uncommon. For the most part, people assume either that bisexuality doesn’t exist, or that bi people are evil sluts, basically. And these ideas are heavily reflected in popular culture. When I was growing up, bi people were practically invisible in the mainstream. And when they were represented, they were usually killing someone. Literally. Like, have you ever noticed that bisexual people in movies are almost always sex-crazed demonic murderers? Just to throw out a few examples: There’s the classic thriller Basic Instinct, where Sharon Stone plays a depraved, murderous bisexual; or Jennifer’s Body, where Megan Fox engages in a sex ritual that transforms her into a bisexual homicidal demon; or House of Cards, in which the protagonist Frank Underwood is a manipulative, sexually fluid politician who casually kills anyone who gets in the way of his rise to power. And these are just the most obvious examples.

In an article for Slutever, writer Kristen Cochrane shed light on the tired stereotypes and tropes that are projected onto bisexuals. Her essay explored how negative representations of bi people reinforce hegemonic definitions of good and evil—good often being equated with no

rmativity and dominant values, and evil often being equated with transgression. And bisexuality is often presented as the ultimate threat to normative order and humanity’s very existence. To quote Cochrane:

Bisexuals are often characterized as the villain. A quick Google search led me to find a TV Tropes page that discussed the recurrence of the “Depraved Bisexual” in moving-image media. It’s a simultaneously funny yet tragic encyclopedic web page which outlines how the “Depraved Bisexual” is different from the “Psycho Lesbian” trope. Instead of being an angry, crazy lesbian, the “Depraved Bisexual” is always down for sex, and will take whatever they can, whenever they can. These assumptions lead to many people feeling entitled to ask the “Depraved Bisexual” about their sex life (e.g. if you are female, how you have sex with other women, “Does this mean you will have a threesome with me and my girlfriend?” asks the straight guy, usually, etc.)…It is evidentiary of the objectification of queer people.

In 2016, GLAAD’s annual “Where We Are on TV Report,” analyzing the state of LGBTQ characters on scripted television, showed that bi characters are on the rise, making up roughly 30 percent of recurring LGBT television personalities. Clearly, this sounds like progress. However, while gay and lesbian TV characters are increasingly being portrayed in a way that doesn’t make their sexuality a primary and morally reprehensible element of their character, bi characters are still often represented as two-dimensional clichés. There are four main tropes surrounding bisexuality, as identified by GLAAD: (1) characters who are depicted as untrustworthy, prone to infidelity, and/or lacking a sense of morality; (2) characters who use sex as a means of manipulation or who lack the ability to form genuine relationships; (3) associations with self-destructive behavior; (4) treating a character’s attraction to more than one gender as a temporary plot device that is rarely addressed again.

The truth is, I’ve always been hesitant to identify as bisexual, and not just because of the demonic murderer association. For one, the word “bisexual” just sounds a bit old-school at this point. A lot of people that are in theory bisexual—in the sense that they are attracted to both men and women—are also attracted to people in other gender categories, like trans women, trans men, and any number of the other roughly nine thousand confusing Facebook gender options, like snake gender or whatever the Gen Zs are into.

For the most part, people either think bisexuality is “just a phase”—like an “I did a lot of ‘experimenting’ [read: drugs] in college” type of thing—or they assume bisexuality is simply a stepping stone on the way to a gay identity. Or, worse, they think identifying as bi just means you’re in gay denial. That last one is especially true for men. Take my friend Joseph, for instance. He’s a twenty-six-year-old artist who predominantly sleeps with guys. However, like me, he occasionally finds himself face-to-face with a pussy. Nothing to make a fuss about. However, when asked about his sexual identity, he always just says he’s gay, “because it’s easier.” He said that in the past, when he’s identified as bi, people just assumed he was too embarrassed to wear a badge of gayness. So, to avoid presenting an image of shame, he just sticks with gay. I get where he’s coming from, but it’s still a bummer.

Some people assume that if you identify as bi, you have to be simultaneously involved with both genders to be truly satisfied. Basically, your life is a never-ending threesome, or else you’re bored. This leads to the erroneous belief that bisexual people must be either nonmonogamous or promiscuous (which is actually true in my case, so I’m not a great example, whoops). Also, if you’re a bi woman, sometimes a guy will assume that you’re just hooking up with another woman as a tactic to get his dick hard. Because we all know that female sexuality really only exists as an aphrodisiac for men.

After I started eating pussy on a regular basis, I felt like I needed to find a new way to identify my sexuality now that straight was no longer cutting it, and so began my quest for the perfect trademark. For a second I considered “straight but with a girlfriend,” which Alice quickly vetoed. Then came the awkward explanation “I just have a very egalitarian vagina.” Also not popular. After that I tried out “down for whatever” for a while. I liked how casually confident it sounded, like something you’d say with a shrug while sipping a martini. However, people at parties kept misinterpreting this as me wanting to immediately blow them in the bathroom, so I unfortunately had to extinguish that as well.

On some days my search for an identifier seemed irrelevant. Fuck it, I’d think. I’m a liberated sexual butterfly—who cares what word I use? But on other days I felt like a sexual orphan, not totally at home in the gay or straight communities. Essentially, homeless.

Words are power. Having the right language can help us to carve out our place in the world, whether that label be doctor, mother, slut, athlete, groupie…whatever. Labels can build communities and empower through solidarity. But other times, they can limit us. Like, just because you identify as gay, that means that you’re never, ever allowed to sleep with someone of the opposite sex? Even if you’re high on ecstasy? Come on. If cool, smart, nice, hot people come in all shapes, sizes, ages, races, and genders, then why should we assign ourselves some dumb label that will only inhibit us from tasting the rainbow?

And then it came to me one day, while I was attempting to do Pilates. I was bending over to touch my toes, and I thought, Gosh, I’m so flexible. Like a classic epiphany, it hit me.

That was a lie. But “flexible” is a word I’ve only recently adopted, and it’s the first word that instantly felt right in association with my sexuality. Flexible—someone whose sexuality can bend and change, even accommodate; a state so elastic that it’s impossible to classify. Sure, in a sense, “flexible” is still a label, but it’s also kind of not, somehow. It’s a nonlabel label? It describes an identity without subscribing to an identity. It’s like the sex equivalent of being agnostic. It’s the ultimate noncommitment (and you know I’m a commitmentphobe).

In the past, there’ve been a variety of other labels that people have adopted in order to separate themselves from the norm and to assert that sexuality exists on a spectrum. For instance: omnisexual, pansexual, polysexual, queer, sexually fluid, gay-for-pay, et cetera. I know many people who identify as queer, and who get a lot out of feeling like part of that community. However, all these identifiers are a bit too heavy-handed for me, personally. They don’t stand purely for the freedom of desire; rather, they represent lifestyles that come with a prepackaged set of ideas. And I’m wary of that baggage. I hate the idea that if I tell someone I’m queer, they already have all these predetermined ideas about me—what music I like, what bars I hang out in, that I go to poetry readings at feminist bookstores and braid my armpit hair and am furiously vegan…or whatever.

In a Big Think interview about religion, the famous astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson said, “I don’t associate with movements—I think for myself. The moment someone attaches you to a philosophy or a movement, they then assign all the baggage and the rest of the philosophy that goes with it to you. And when you want to have a conversation, they will assert that they already know everything important there is to know about you because of that association.”

What I’m getting at with this longwinded rant is, it feels good to remove my sexuality from the burden of any type of dogma. I’m not exaggerating when I say that I flip my Tinder settings back and forth from men to women depending on how I’m feeling that day. Sometimes it genuinely feels like my sexuality changes with the fucking wind.

Sexual Yoga

In 2018, we pat ourselves on the back for being sexually progressive, gender-defiant, morally superior posteverything children of wokery. However, new studies show that sexual fluidity existed long before the dawn of the feminist blogosphere. The idea that not everyone is either exclusively straight or exclusively gay, or consistently somewhere in the middle, isn’t a new one. The revolutionary sex researcher Alfred Kinsey developed the Kinsey scale way back in 1948, which placed sexuali

ty on a continuum of 0 to 6: “exclusively heterosexual” to “exclusively homosexual.” Since then, there’ve been various liberal pockets of society in which people have accepted ideas about sexual fluidity, from the free-love hippies in the 1960s to the rise of queer culture in San Francisco in the ’90s. However, to our credit, only in recent years have we begun to accept sexual flexibility in a broader, more mainstream social sense. In other words, sexual fluidity is no longer a fringe idea—it’s now used by Calvin Klein to sell underwear. When we can capitalize on our bisexuality, we know we’ve truly made progress.

Today, there’s a growing body of social science research indicating that a substantial number of people experience fluidity in their sexual and romantic attractions. Reliable data from several recent studies found that 6 to 9 percent of American men and 10 to 14 percent of American women describe themselves as not completely heterosexual—they wouldn’t necessarily identify as bisexual, but they fall somewhere in the gray area. (For reference, 1 to 2 percent of the male population is gay, and 1 percent or less of the female population is lesbian.) Yes, the vast majority of the world is still straight—even though it really doesn’t seem that way if you live in New York—but the verdict at the core of much of this new data is clear: Sexual variability is a natural part of being human.

Slutever

Slutever