- Home

- Karley Sciortino

Slutever Page 2

Slutever Read online

Page 2

In our postwoke social-justice Millennial whatever, there is no excuse for men to not have a thorough understanding of the nuances of consent. Today more than ever we should hold men accountable for their actions, and to a high sexual standard. But as women, we infantilize ourselves when we don’t take responsibility for our own actions in the bedroom. We have to be able to assess the difference between assault and discomfort. Of course, I’m not saying that if you’re a legitimate victim of sexual abuse you should just “get over it.” (It feels relevant to note that, often, people who are sexually abused call themselves “survivors” rather than “victims,” in an effort to move away from the idea of the passive female victim who’s there for the taking.) But we decide what moments in our lives we give power to. We write our own stories. We can decide to define ourselves by our worst experiences—to become victims rather than survivors—or instead, after something bad happens, we can learn from it and move forward. Because realistically, being a fragile victim is just not on-brand for the modern slut.

If I want to reap the benefits of slutdom, I have to have a thick skin. If I want sexual freedom, I have to be able to say no. Slut power is about freedom, but it’s also about taking responsibility. The world is not a safe space. There is no such thing as safe sex. We are not victims, we are predators.

Cum to the Dark Side

For decades, feminists have been divided over what should become of the word “slut.” There are essentially two camps. The first camp believes that we should eradicate use of the word altogether, arguing that when women call each other sluts—even when it’s in an lol feminist bonding way—we’re perpetuating slut-shaming and so-called rape culture. It’s like when Tina Fey’s character in Mean Girls tells the group of high schoolers: “You all have got to stop calling each other sluts and whores. It just makes it okay for guys to call you sluts and whores.” While Mean Girls is basically my bible (I clearly can’t go three pages without referencing it), I don’t agree with that sentiment. I’m part of camp two, which posits that rather than rejecting the word, we should reclaim it. Historically, many pejorative words have been reclaimed—from “queer” to “butch” to “fag” to “bitch”—by the communities that experienced oppression under those labels. So why should “slut” be any different? It’s naive to think that we can simply abolish a word from the social lexicon because it’s “mean.” (And why would anyone want to get rid of such a wonderfully depraved word, anyway?) Instead, we should take ownership of the slut label, and subvert its negative connotations. Reclaiming a word gives it less ability to harm, and increases its power for provocation and solidarity.

The great feminist slut divide began back in the early nineties, when the Riot Grrrl feminist punk rock movement became the first group to attempt to reclaim the word. I was in my early twenties when I discovered the Riot Grrrl band Bikini Kill, and I remember vividly the first time I saw that iconic photo of singer Kathleen Hanna with “slut” scrawled across her stomach in red lipstick. She looked so impossibly cool. And not only was her message immediately effective, it was also just really funny. Like, girl didn’t give a fuck. In that moment, I realized that it was possible to hijack a word intended to hurt you, and reappropriate it as an instrument of power and irreverence.

I felt similarly the first time I saw a video of Annie Sprinkle’s performance art piece Public Cervix Announcement. In the performance, Sprinkle—the legendary artist, porn star, academic, and sex educator—sat on a chair with her legs spread wide, casually inserted a doctor’s speculum into her vagina, and then invited audience members to come look at her cervix with a flashlight. Pretty epic. She did this in more than a dozen countries throughout the nineties, in front of thousands of people, always with a big smile, cracking jokes. When I saw the video, in my early twenties, I was in awe of how playful the whole thing was. Sprinkle—who self-identifies as a “slut goddess”—was radical in her ideas about sexual exploration and slutty acceptance, but her rebellion had so much joy and levity in it. She was the ultimate antivictim. I was like, Whoa, feminism can be funny? Who knew?!

But not everyone was on the slut train. People in the other camp—the “anti-sluts,” if you will—argued that we should reject the word because it illustrates how, historically, women have been categorized based on their sexual relationships with men. They argued that, while embracing the slut persona might be chill and empowering within your enlightened social circle of feminist bloggers and their beta-male entourages, the rest of the world basically doesn’t get the joke. So you might think you’re being funny, but you’re actually perpetuating the sexual double standard. Essentially, this camp believes that in a world where women are hypersexualized, embracing the word “slut” is actually more of a surrender than a radical act of resistance.

That dispute—over whether, by being slutty, we are empowering ourselves or just shooting ourselves in the vagina—has been central to the feminist divide for a long time, but it hit a peak in the early 2000s. As you likely remember, this was the era of Girls Gone Wild, striptease workouts at the gym, the “landing strip,” and Paris Hilton casually flashing her labia to strangers. In reaction to this, writer Ariel Levy authored Female Chauvinist Pigs: Women and the Rise of Raunch Culture (2005). The book was intended as a wake-up call to women, and essentially argued that the hypersexual female culture that’s supposedly “empowering” is actually just women taking part in their own objectification. She was basically saying that the freedom to be drunk at da club in Manolos with your vag out wasn’t the freedom that Gloria Steinem had in mind.

And that’s probably true—the vision of the future painted by the pioneers of feminism likely had more to do with women in higher education than it did with paparazzi pussy shots. But like, why are the two mutually exclusive? Why can’t I get a PhD and also jerk off in front of a webcam for money on the weekends? Why can’t sluts and nonsluts live together in harmony? Why is it unfathomable that humor and irreverence are valid modes of resistance? At the very least, it sure beats being offended by everything.

While I do think the word “slut” should be reclaimed, I should be clear about what I mean by that. The word “reclaim” is associated with redemption—to reclaim is to recover, to reform, to civilize. That’s not exactly what the goal is with “slut,” at least in my opinion. We don’t want to simply reverse the idea of being a slut from being “bad” to being “good,” or from unacceptable to acceptable. There is something bad about being a slut—something naughty, controversial, and unpredictable—and I don’t think we should lose that. Men don’t have to be good, so why should women? The idea that female sexuality is entirely righteous, or that we have a better handle on controlling our sexuality than men, is a great societal delusion (and one that is sometimes perpetuated by feminism). To totally flip the meaning of “slut” into something that’s solely positive or empowering denies the darkness that’s inherent in slutdom, which is part of what makes it so sexy.

Of course, we want to move toward a society where women aren’t slut-shamed and can express themselves without fear. But I think it’s possible to cultivate a society that permits healthy sexual exploration, while also maintaining the taboo and transgressive elements of slut life. Like, my goal isn’t to be good or normal or accepted. My goal is to be free. (And maybe also to troll society a bit in the process, for good measure).

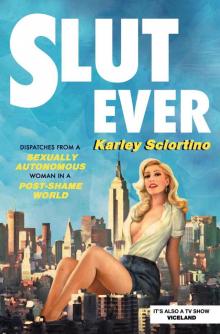

I’ve been writing and ranting about sex and relationships for more than a decade, and have never been good at sitting on the sidelines, observing the action from an objective distance. I prefer to dive into a world headfirst, to chronicle my experiences from the inside. This book is no different. Slutever is a first-person account of a modern, young(ish) woman navigating sex, love, casual hookups, open relationships, boyfriends, girlfriends, bisexuality, BDSM, breakups, sex work, sex parties, and a whole lot of other slutty stuff, as told from the front lines. This is not a self-help or a how-to situation—god no, I wouldn’t put you through that. This is more of a call to arms, a

confessional memoir, a slut manifesto, as told by a hedonistic, sex-radical libertarian slut in a pink PVC minidress. This is a story of a slut who lives happily ever after—or at least one who doesn’t get eaten by zombies.

CHAPTER 1

MADONNA THE WHORE

Sex Education

What I’m about to say is so predictable that it verges on cliché: I grew up in a conservative Catholic family. Yes, I am a slutty Catholic girl. How unoriginal.

I can’t say for certain that my parents’ insistence on me not having sex directly resulted in me wanting to have sex with everyone all the time forever, but I like to think that it did. Of course, there is no single defining truth. There are a million defining truths. But since I’m the one telling this story, I control the narrative. And in my version, growing up Catholic made me a slut. And spending every Sunday in church, gazing up at a giant stained-glass image of the stations of the cross—which, let’s be real, is straight BDSM—directly resulted in me becoming a dominatrix. And I’ll definitely credit the Madonna-whore complex for my later foray into sex work. It all fits together so nicely.

Today, I relish knowing that two of my sex-radical heroes—those being none other than pop icon Madonna and the controversial pro-sex feminist Camille Paglia—grew up in devout Catholic, Italian American families, just like myself. A coincidence? Probably not. When I think of growing up Catholic, I’m always reminded of a quote from Paglia, in an essay she wrote about Madonna in 1990: “Madonna’s provocations were smolderingly sexy because she had a good Catholic girl’s keen sense of transgression. Subversion requires limits to violate.” In other words, nothing is sexier than being told no.

Some of my earliest memories are of my mother talking to Jesus. This wasn’t exactly standard praying; this was more of a casual conversation. Like, “So, Jesus, should I make chicken or pasta for dinner tonight?” Ya know, just shooting the shit. At one point, she was regularly suggesting to the son of God that Elisabeth Hasselbeck should win Survivor. She loved giving J-dog her unsolicited advice.

Neither my dad nor my brother and I ever joined in on her divine monologues, but we’d listen, and it felt like we were somehow included, sort of like our family had its own imaginary friend with whom only my mother could liaise. The only time it bugged me was when I had friends over—the presence of a neutral party always seemed to recontextualize her Jesus convos from being cute and kooky to straight-up batshit. “Mom,” I’d whine. “Me and Sarah are trying to watch The Real World. Go talk to Jesus in your room!”

“This is my house,” she’d hit back. “I’ll talk to Jesus wherever I want.”

“Well, I’m sure Jesus is busy!” I’d shout. “Maybe you should try playing hard to get.”

I grew up in a small town in upstate New York—so small that it’s technically not even a town but a hamlet. This is where both of my parents were born and raised, and after meeting and falling in love in high school, they married and raised me and my little brother there. To give you a mental picture, it’s the sort of place where deer cause traffic jams and people think evolution is a movie starring David Duchovny. It’s pretty much your average apple-farming town located on the Hudson River, and while it’s undoubtedly beautiful, for a kid it’s pretty boring, because nothing ever “happens” there. When I was in high school, for fun my friends and I would hang out in the parking lot of the local grocery store, listening to Britney Spears CDs on repeat (or Green Day if we were feeling alt). On weekends there would usually be a keg party in one of the town’s sprawling apple orchards, and we’d get wasted on warm beer and cough syrup and have sex in pickup trucks. That was pretty much the extent of my cultural experience until the age of eighteen. The town has changed quite a lot since I was little—now there’s some city overspill, and a few new restaurants that serve craft beer and artisanal whatever, but when I was growing up it was almost exclusively second- and third-generation Italian Catholics, and there were only a handful of places to eat, all of which had names like Tony’s and Sal’s and played exclusively Frank Sinatra.

My mother worked part-time as a receptionist at a dentist’s office, and spent her free time volunteering as a religious educator and watching the Eternal Word Television Network (aka “the God Channel”). When my dad wasn’t working long hours at his office job or screaming at the TV, he devoted his time to the Knights of Columbus, an all-male church organization that I’ve recently realized might actually be a cult. They would do things like run the beer tent at the town bazaar, host spaghetti fundraisers for people whose houses had been crushed by falling trees, and a variety of other top-secret Jesus stuff that my dad never talked to us about. Besides God and football, my dad’s greatest passion was saving money. I have an early memory of him teaching me how to wipe my butt, and explaining that “Using any more than three sheets of toilet paper is a waste of money.”

Though our family was never poor—we were the middlest of middle class—my dad refused to spend extravagantly on anything, for any reason. Every summer, when my friends’ families went off to Mexico or Europe on vacation, my family went to New Jersey. New Jersey, every year, without fail, from before I can remember all the way until after I graduated high school. To be fair, I did always enjoy our Guido family trips to the Jersey Shore, but by the time I reached double digits, I understood on some level that our fried shrimp–centric vacations were missing an element of glamour.

It’s no real surprise that I never got the “sex talk.” However, there were a few times when I came home from school to find that my mom had taped a show off the God Channel where either a priest or a nun was preaching about the benefits of chastity. She’d then force me to watch it while she sat next to me on the couch, nodding her head in slow motion. Once, in middle school, I had something close to a mental breakdown after she taped Mother Angelica’s special on the joy of virginity over the new episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

I’m not a scientist, but it seems obvious that when someone is constantly telling you not to have sex, it results in you thinking about sex literally every second. Starting in my early teens, sex became my ultimate fascination—what about it, I wondered, was so special as to make it forbidden? It didn’t help that, since the age of about ten, I was a low-key masturbation addict. I would spend hours in the bath, my butt pushed all the way to the end of the tub, legs in the air, so as to position my clit right under the flow of the faucet. If my memory serves me well, most of my masturbation fantasies at that time centered around the girls in bikinis who I’d seen in rap music videos (perhaps because that was one of my only sources of erotic material, but also maybe because my vagina was and seemingly always will be a teenage boy). Roughly every fifteen minutes my dad would bang on the bathroom door, asking me what was taking so long and telling me to stop wasting water. Looking back, it creeps me out to think that he likely had somewhat of a clue what was going on in there.

But I’m pretty sure I was a pervert even before I had any idea about sex or masturbation. Case in point: When I was just five years old, I developed a fixation on these twin girls in my kindergarten class, who had just moved to our town from China. They were in the process of learning English and could barely communicate, which to a bunch of five-year-olds definitely made them seem like “others.” Well, for some reason, I started playing out these long, detailed fantasies in my head where I was physically torturing these twins—tying them up, slapping them, making them cry, et cetera. These fantasies weren’t explicitly sexual, but I definitely was both entertained and excited by them. This went on for the whole school year. If I wanted to pass the time while on the bus ride to school, or while sitting in church, I’d just close my eyes and think about tormenting the Chinese twins. It progressed to the point where if I had the chance to kick one of them under the table in class while no one was looking, I would. And they couldn’t even tell on me, because they couldn’t speak English. It was the perfect crime. Although I did get in trouble more than once for opening the door while one of th

em was in the bathroom, even though the red “stop” sign was clearly visible. At the time I had no context for these twisted daydreams, but I did understand on some level that they were strange, and not something I should casually talk about during playground gossip. But looking back on it years later, I’m like…Wait, was that a sex thing?

At the age of thirteen, I made a formal pledge to my mother and grandmother that I would wait until I was married to have sex. In exchange for this ultimately empty vow, I was given a promise ring by my grandmother—fourteen-karat gold, containing a tiny diamond—which was my most prized possession until I lost it while swimming in a lake (which coincidentally happened not too long after I was railed for the first time, which I of course interpreted as a punishment from God). At the time that I made the promise, I truly believed it. I was a big Jessica Simpson fan back then, and since she was so avid about waiting until marriage, I figured that I might as well at least try. Plus, both my mother and grandmother had made it very clear to me that if a woman chose to have sex before marriage, she would spiral out of control and become a homeless crack-addict spinster who no man would ever dream of marrying, or something along those lines.

Suffice to say, the Madonna-whore complex was instilled in me from a young age. The term “Madonna-whore complex” was first coined by Sigmund Freud—aka the father of psychoanalysis, who most women today look back on with an eye-roll emoji—and describes a dichotomy in which men view women as either saintly, virginal Madonnas, or sexual, skanky “whores.” Freud believed this complex emerged in men because of developmental disabilities, but others attribute it to the way in which women are represented in mythology and Judeo-Christian theology. And as someone who was forced to read the Bible cover-to-cover in my tweens, I can vouch for the fact that biblical women are either undefiled, bride-worthy maidens or thirsty skanks. And since I had no interest in becoming persona non grata to the entire male population at just thirteen, my vague game plan was just to date the bathroom faucet until I met “the one,” and then let him unwrap me like the gift that I was on our wedding night.

Slutever

Slutever