- Home

- Karley Sciortino

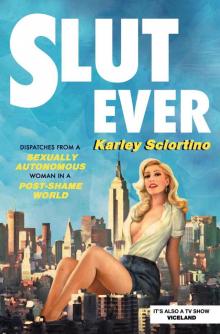

Slutever Page 3

Slutever Read online

Page 3

Yeaaah, that didn’t pan out. I lost my virginity at sixteen, to my boyfriend of a week. He was in the grade below me, and was freakishly tall and scrawny, with these big Dumbo ears and an Adrien Brody nose. Shoulder-length brown hair, sunken eyes, freckles. His nickname, in a coup de force of imagination, was Bones. He was so beautiful, I could puke. I’m pretty sure the way he looked informed my “type” for the rest of my life, because almost everyone I’ve dated since then looks like some version of an insectile human line drawing. (After the first time I introduced Bones to my mom, she scolded, “Karley, I’ve seen him with his mother at the grocery store. I thought he was a special needs child.”) I liked that when I hugged him I could wrap my arms all the way around his chest and almost back again—I can’t explain why, but it just felt comforting, like how I imagine a wrestler feels when his opponent enters the ring and he realizes he’s got a solid thirty pounds on the guy.

Bones and I boned in the woods behind the football field one day after school. (It really doesn’t get more teen-movie than that.) It lasted about thirty seconds. We hadn’t even gotten all of our clothes off before Bones came into his baggy blue condom. It didn’t even hurt like everybody said it would—probably because I’d been casually sticking shampoo bottles up there for multiple years at this point—but it didn’t feel good, either. It just kind of…was. But I wasn’t bothered about the whole pleasure aspect of sex at this point. It’s sort of like when you first start drinking alcohol—you’re not concerned with the taste or quality, or any of the subtle or ostensibly sophisticated pleasures of drinking. You’re just trying to get fucked. Well, that’s how I felt about sex.

After the anticlimactic football field encounter, I didn’t feel as though I’d learned what sex was like—rather, I felt like I’d learned what sex was like with Bones. Now the quest became to discover what sex was like with, ya know…everyone else. As you can imagine, my parents were really strict, which threw a bit of a wrench in my newfound teen-ho aspirations. I always had the earliest curfew of all my friends. Once, when I asked if I could go to a high school baseball game, my dad responded, “Are you kidding? I know what happens at baseball games. I’m not paying for an abortion.” Since my parents didn’t let me have boys over to the house, I had to get experimental with finding alone time with guys. This meant that my high school years involved a lot of sex in cars, on baseball fields after dark, in parking lots—all very classy. The sex, of course, was terrible—but so fun. At the time I was into younger guys, and when you’re sixteen and fucking guys younger than you, they tend to be virgins (and conveniently desperate). By the end of my high school career, I’d taken six virginities. I was and am still too proud of this.

During those early slutty adventures, there was a part of me that I suppose felt something close to guilt. I understood that what I was doing was “bad”—at least, according to everyone around me, my church, and most of what I’d seen on TV. But it felt thrilling to be bad. It’s basic psychology: It’s fun to do bad things (I think the young meme prophet Latarian Milton said that). And with all that shame and sin and suppression, we Catholics have a lot to work with. To quote John Waters, “I thank God I was raised Catholic, so sex will always be dirty.”

After I entered into what I like to call my “teen sex-mania phase” (also known as junior year), on multiple occasions, close friends of mine sat me down for Dawson’s Creek–style “We’re worried about you” conversations. Apparently having more sexual partners than you can count on one hand by eleventh grade warranted an intervention. At school there was a never-ending rumor that I had “the clap”—though no one seemed to have a firm understanding of what the clap actually was. At first I just brushed it off. They’re jealous, I told myself. But it was difficult not having friends who I could confide in about these experiences. (Remember, this was early internet days, so I couldn’t just go to LonelySlutsAnonymous.org or whatever and instantly find a crew of like-minded aspiring deviants; you younger Millennials have it so easy.) There seemed to be an invisible line between talking and thinking about sex, and actually having it. I didn’t understand why it was okay for my friends and me to sit around reading Cosmo sex tips together, which we did religiously (thanks to Cosmo, we all grew up thinking that every relationship problem could be fixed by giving your boyfriend a boob massage), yet when I’d say, “I blew Scott in the shed where they keep the life jackets at the reservoir,” my friends would be like, “There’s a high chance you have AIDS.” There was definitely a dissonance there. But to be fair, that was on trend at the time. Remember, I was in high school when Britney Spears was writhing around on the floor with a snake singing, “I’m a slave for you,” while simultaneously saying that she was waiting until marriage to have sex. It was the Sex and the City era, but a few miles north of Samantha, the parents in my town were petitioning to prevent the health department teaching us how to put a condom on a banana. It was a confusing time to be a slut in training.

During the summer before senior year, after I got caught spending the night with a twenty-nine-year-old apple farmer, my parents sent me to a Catholic therapist. Predictably, the therapist tried to further convince me that my sexual behavior was problematic. She said that I used “sex as a weapon” against my family, and against myself. In my rebellious teenage mind, however, I thought the concept of sex-as-weapon sounded really cool, like the ability of a sexual superhero or something. Like my vagina had a machine gun. It could be worse, I thought.

But I wasn’t totally immune to the critique. I (unfortunately) am not a sociopath, and after a while, some of the slut-shaming started to get to me. For instance, on the night of the junior prom, one of the most popular boys in my grade brought a blow-up sex doll to the afterparty and wrote my name on its forehead. For the rest of the evening all the jock football bros passed around the doll and mimed having sex with it, finding no end of amusement in this. I was like, Wow, I do have a gang-bang fantasy, but this is not how I envisioned it would play out.

In hindsight, so much of this early mockery and social monitoring seems pretty trivial. I also acknowledge that I was objectively “popular,” and had life a lot easier than many kids at my school, for instance the girl everyone called Shrek (although to be fair, it was an accurate representation of her). But when you’re sixteen, it’s hard to imagine a world bigger than high school. You have this idea that what’s said about you in the rumor mill—be it good or bad, true or fictionalized, or somewhere in between—is somehow etched into your future identity, and that you will never meet another person who doesn’t have a PhD in everything you’ve ever done and that’s been said about you. It can be quite paralyzing.

There was one particularly dark moment that became a kind of turning point for me. It was senior year, and one of my best friends, Courtney, was having a house party while her parents were out of town. We all got zombie wasted—as you do when you’re seventeen and still working out that nine vodka shots in an hour might be too many—and in my drunkenness, I ended up banging Courtney’s older brother. He was a couple of grades ahead of us in school, and was home visiting from college. I didn’t think it would be that big of a deal (slash I didn’t think at all), but when word spread through the party that I had disappeared into his bedroom, Courtney went into full-on Real Housewives mode. To make a long story short, she barged into his room, grabbed my dress and shoes from his floor, and promptly marched outside and threw them into a bush. I then had to run outside to get my clothes wrapped in just a towel, while the rest of the party looked on, half laughing, half horrified. As I was clawing my way through the shrubbery, searching for my Payless chunky platforms, Courtney and my other closest friends stood watching me from the sidelines, united in bitchface. The night ended with Courtney literally spitting at me in the middle of her driveway, in front of a crowd of like thirty people. For a week afterward, none of my friends would talk to me in school. I felt like I was starring in a teen movie version of The Scarlet Letter, except instead of a scarlet A,

I donned a more early-2000s symbol of shame: a Victoria’s Secret thong poking out of my super low-rise jeans, obviously.

To this day I still don’t understand what the big deal was. Apparently people don’t like it when you fuck their family members? It was like that episode of Sex and the City where Charlotte and Samantha have a major falling-out after Samantha fucks Charlotte’s brother. For the record, everyone is invited to fuck my family members, as long as you’re polite about it. But what I learned from the brother-banging incident—and all the smaller incidents leading up to it—was that being a girl who’s casual about her slutcapades does not sit well with most people. In fact, it often inspires rage. After that, I decided it was probably better to keep my sexual exploits on the DL. And thus spawned my double life—the Clark Kent me that I presented to the world, and the real, slutty superhero me that only came out at night (and sometimes during lunch hour).

By the time I finished high school, in 2004, Clark Kent me was killing it. I graduated seventh in my class, was an editor of the senior class yearbook, captained both the varsity soccer and basketball teams, played the lead in the school play (Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, naturally), was a senior prom queen nominee (still haven’t recovered from the loss), and was just generally an all-around star student, friend, daughter, and athlete, with an undoubtedly irritating level of enthusiasm for all of the above. I even made it through most of my final school year without inciting a single sexual intervention from my friends or family members. Yet, leading up to graduation, the conversations with my parents about my college plans never went down so well. My dad was really pushing for me to go to West Point, the United States Military Academy, where the students are officers-in-training (or “cadets”), where boot camp is required before entry, and where the tuition is fully funded by the army in exchange for an active duty service obligation upon graduation. Right. Despite repeatedly telling my dad that I wanted to be a Hollywood actress and not a soldier, hello, I still was forced to visit the West Point campus. “Dad, as if I’m gonna go to a college that requires me to wear fatigues,” I whined, stomping my Uggs in protest.

Stronger than my aversion to wide-leg camouflage pants, however, was my desire to just get out—to remove myself from the busybody social monitoring that anyone who grew up in a small town is all too familiar with. This reminds me: A few years ago, I was listening to Dan Savage’s sex advice podcast, Savage Love. One of the callers was a teenage boy from somewhere in the Bible Belt, and his question to Savage was essentially this: I just graduated from high school, I’ve come out as gay, and it’s not sitting well with my friends and family. What can I do to make people in my town accept me? Basically: How can I make my life better? And Savage’s answer was one that I didn’t expect. I expected him to talk about self-acceptance, and therapy, and secret gay mating call hand signals or something. But instead, his answer was: Get on a bus and move to San Francisco. Or Seattle. Or literally anywhere with a vibrant gay community. His point was that while it’s nice to hope that one day the world will be more accepting and we’ll all be able to channel our inner freak snowflakes or whatever, in the meantime you have to live with the reality that most people in your town just think you’re a weird fag. A harsh response, for sure, but I appreciated that.

And I think you can apply that to slutdom, too. Like, there are some people in the world who are just never going to accept or respect a person—particularly a woman—who has a lot of sex, or who just talks openly about sex, and it can be a waste of energy to even try to change their minds. But I mean, whatever, not everyone has to like you, right? (In fact, if everyone did like you, it would mean that you were worryingly inoffensive, aka boring.) Listening to Dan Savage made me so happy that I left home at eighteen, even though I didn’t understand the enormity of my decision until later on. It was as if, like my mother had always told me, I truly had a guardian angel on my shoulder, watching out for me. Except my guardian angel just happened to be one of the biblical whores, whispering into my ear: Go forth, young slut. Find your people.

Sluts Who Dumpster-dive

Unsurprisingly, my parents were both horrified and confused when, instead of opting for target practice or entering a mediocre state school to study the complex art known as “communications,” I moved to London just weeks after finishing high school. I ostensibly went there to study theater, and was enrolled as a drama major at a university in London. But I also just liked the idea of putting an ocean between me and my parents. And so I applied for a passport, got on a plane, and left the country for the first time, on a delusional mission to become a successful playwright and thespian. Things didn’t exactly go as planned. You know that cliché: the more overprotective the parents, the more likely the kid is to treat college like a binge-drinking, amateur gang-bang bacchanalia? Well, that was basically my experience. Minus the college part.

It’s hard for me to recall the exact headspace I was in when I moved away. But what I do know is that, up until that point, I’d been a person who really cared. I always got good grades, always did the extra credit, was never late to practice, and I tried, for the most part, to seem like a respectable human being. And then suddenly, I just couldn’t care anymore. I started partying every day, skipped almost all my classes, slept around (uncircumcised dicks—a new discovery!) and ended up dropping out of college after just one semester. But I liked London, and wanted to stay. Or at least, I didn’t want to go home.

Like everyone does, growing up, I’d often imagined my future. There were a number of things that I thought I might grow up to be. An actress was my first choice, but I also thought I might be a news reporter, like Diane Sawyer, with her perfect blond blow-out and crisp Oxford shirts. I briefly entertained the idea of being a lawyer, because I loved Ally McBeal. I even, for a while, considered paleontology, on the sole basis that I frequently jerked off thinking about Jeff Goldblum in Jurassic Park (who, I worked out later, didn’t even play a paleontologist in that movie). Never once, however, did I envision myself growing up to be a vaguely ketamine-addicted degenerate squat rat who ate out of the garbage. Life is funny like that.

When you’re an unemployed eighteen-year-old five thousand miles from home with no money, prospects, or responsibilities, you end up in some unique situations. One night, I found myself high on ecstasy, on a party boat in the Thames River. I was dating a guy I’d met at university—a sexy, freckled musician named Sam, whose band was serenading the seasick partygoers, and I’d tagged along for the ride. This is where I serendipitously met Matthew, an artist in his early twenties whose soul I instantly connected with on a profoundly drug-induced level. Matthew stuck out like a sore thumb—he was six foot three, but more like six foot six if you counted his hair, which was a flat-top of brown curls that shot straight out of his head as if he’d just been electrocuted. He was wearing dark eyeliner, lipstick, and a tattered cape, and looked like some sort of urban shaman-slash-goth drag queen. He told me he was squatting in an abandoned elevator factory in south London with a group of nine other artists, musicians, and writers. Squatting, he informed me, was the act of occupying a building that you don’t own. So basically you find an empty building, move in, change the locks, and then just stay there rent free until the owner decides he wants you out and takes you to court. “You should totally come visit,” Matthew said excitedly. “We make these giant feasts out of food that we find in the bin!” If I had been even 1 percent less high I probably would have passed, but in the moment it sounded very exotic. Or at the very least, not touristy.

The following week, I went over to the squat for what Matthew referred to as a “bin banquet.” The rule of the meal was that you couldn’t pay for anything. This meant salvaging recently out-of-date packaged food discarded by supermarkets, getting salt and pepper sachets from McDonald’s, and stealing bottles of alcohol. That night, Matthew and his arty squat crew made a five-course meal that fed fifteen people, in their thirty-thousand-square-foot warehouse. It was a perfect art-school avant-gard

e fantasy: acoustic guitars, flower crowns, people rolling filterless cigarettes, people quoting Nietzsche unironically. I think there might have even been a drum circle. Looking back, I understand that, if I had grown up poor, without basic comforts, the idea of eating out of the garbage might have felt less romantic. But I was totally smitten. While the term “squad goals” hadn’t yet hit the zeitgeist back in 2005, I knew instantly, on that first night, that I desperately wanted to be one of their crew.

At this point in my life, I was just sort of floating. Ever since dropping out of university I had been low-key homeless, spending most nights at Sam’s or squeezing uninvited into his band’s crappy minibus as they toured around the country playing mostly empty dive bars. I was essentially being a professional girlfriend, and was beginning to feel like I needed my own life. So when Matthew suggested I should move in with him, I jumped at the offer. (To clarify, Matthew is gay, and thus is a rare character in this story in that we were not boning.) However, moving in wasn’t that simple. See, the squat functioned as a commune, and members shared everything from food to clothing, and adding a new person into the mix meant further splitting the bounty. In order to regulate the number of occupants, each time someone wanted to invite someone new into the house, all the existing squatmates had to vote on whether to accept or reject the applicant. It was essentially like applying to live in one of those Upper East Side co-ops, except the super-gross version.

Slutever

Slutever